Blum & Poe

2727 South La Cienega Boulevard

Los Angeles, CA 90034

310 836 2062

Also at:

19 East 66th Street

New York, NY 10065

212 249 2249

Los Angeles, CA 90034

310 836 2062

Also at:

19 East 66th Street

New York, NY 10065

212 249 2249

Artists Represented:

Alma Allen

Alma Allen

Theodora Allen

Karel Appel

March Avery

Darren Bader

Alvaro Barrington

Lynda Benglis

JB Blunk

Mohamed Bourouissa

Pia Camil

Robert Colescott

Thornton Dial

Carroll Dunham

Sam Durant

Kōji Enokura

Anya Gallaccio

Aaron Garber-Maikovska

Tomoo Gokita

Sonia Gomes

Françoise Grossen

Mark Grotjahn

Ha Chong-hyun

Kazunori Hamana

Julian Hoeber

Lonnie Holley

Yukie Ishikawa

Matt Johnson

Acaye Kerunen

Susumu Koshimizu

Friedrich Kunath

Yukiko Kuroda

Shio Kusaka

Kwon Young-woo

Mimi Lauter

Lee Ufan

Tony Lewis

Linder

Florian Maier-Aichen

Victor Man

Eddie Martinez

Paul Mogensen

Dave Muller

Kazumi Nakamura

Yoshitomo Nara

Asuka Anastacia Ogawa

Kenjirō Okazaki

Anna Park

Solange Pessoa

Harvey Quaytman

Lauren Quin

Umar Rashid

Matt Saunders

Hugh Scott-Douglas

Nobuo Sekine

Penny Slinger

Kishio Suga

Alexander Tovborg

Yukinori Yanagi

Yun Hyong-keun

Zhu Jinshi

Gallery exterior. Courtesy of Joshua White and Blum & Poe Gallery, 2010.

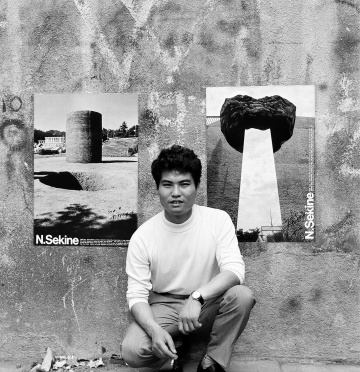

Nobuo Sekine

Broadcasts: Tribute to Nobuo Sekine (1942-2019)

Blum & Poe Broadcasts presents a tribute to the late Nobuo Sekine, one of the central figures of the Mono-ha movement in Japan. This month marks a year since his passing.

Broadcasts: Three Day Weekend Presents "The Gallery is Closed"

Engaging directly with this shared global experience of pandemic-motivated social distancing, Blum & Poe Broadcasts, Dave Muller, and Three Day Weekend present an online group exhibition titled "The Gallery is Closed." A number of artists and members of our community have contributed personal drawings and public signs that announce closure and reflect a multitude of absent voices and voices in waiting.

Solange Pessoa

Broadcasts: Solange Pessoa at Ballroom Marfa

Blum & Poe Broadcasts presents a focus on the practice of Brazilian artist Solange Pessoa, in conjunction with her first US museum exhibition currently installed at Ballroom Marfa, Texas. Like many other museums today, Ballroom Marfa is now closed indefinitely—this Broadcast is intended to share significant work that would otherwise be on view to the public.

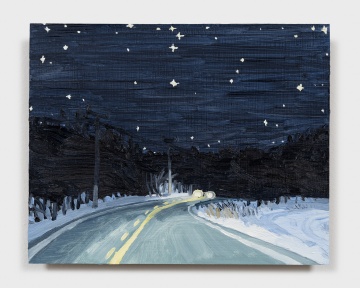

Tom Anholt

Sticks and Stones

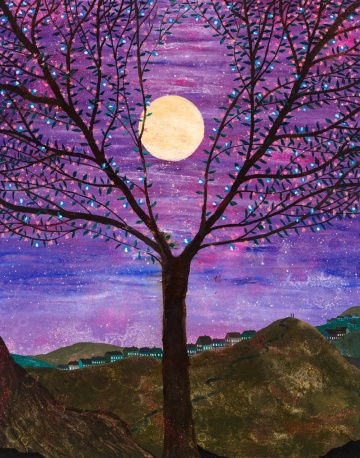

November 4, 2023 - December 16, 2023

BLUM is pleased to present "Sticks and Stones," Berlin-based artist Tom Anholt’s first solo exhibition with the gallery.

Anholt makes paintings that straddle the line between the semiotic implications of representation and the ineffable emotive qualities of abstraction. Referencing the artist’s curated repository of tropes and imaginary settings, each work on linen places a strong emphasis on composition and the hand. This signature style breaks each scene down to its most essential spatial components of form, light, and color—affective gestures that accumulate and transform recognizable symbols.

Partially alluded to in the exhibition title, the symbol of the tree is one of the predominant signifiers in "Sticks and Stones." Formally used as a device around which to build receding depths, "Contemplation" (2023) or "Perfect Day" (2023) depict trees and their branches as dark, snaking lines which route from end to end of the linen’s most forward-pushing interior. Receding from these meandering twigs are mid-plane horizon lines which separate glistening bodies of water from rolling hills. On a personal level, trees also represent the artist’s twin sister Maddy, who began a battle with brain cancer just as Anholt started his first work for this exhibition. That precursory painting, "Twin Branches (For Maddy)" (2023), is a tribute to her, and functions as the narrative beginning of the show. As Maddy’s condition advanced, the artist began to see the person he had known wane—she left this world just as Anholt was finishing the exhibition’s concluding work, "Drifting Away" (2023). Telling a story of resilience and strength, "Sticks and Stones" honors Maddy’s life—capturing the unutterable emotions and simple moments of closeness tied to the universal experience of losing a loved one.

Viewing painting as a healing process, Anholt often takes as his subject matter the types of contemplative pastoral nature scenes favored by painters of the Romantic era. Key elements of these landscape paintings are blue pools of flowing or still water next to vibrant green fields. Each quadrant of the work functions as an abstraction with ambling brush strokes of greater or lesser pigmentation, imitating the natural qualities of light as it reflects. Seeded into these swatches of painterly marks is the occasional tiny figure, calling to mind the allegorical scenes of Caspar David Friedrich.

Most of the vignettes in "Sticks and Stones" take nighttime as their setting, employing the rich, darker palette required to indicate the absence of light. Simultaneously, the moon appears in many of these works—a twinkling orb or crescent that commands attention by means of its striking contrast with its shadowy environment. As much a recurring character as it is a motif or geometric abstraction, this moon unites the splintered factions of the painting schools from which Anholt draws reference.

Like the Romantic painters of times past, Anholt conveys personal sentiment and an interest in the natural world. Like the Abstract Expressionists, he uses gestures that call attention to his medium. Anholt unites art history, allegory, natural imagery, and an emotive palette to under the umbrella of his own visual language.

Tom Anholt (b. 1987, Bath, UK) lives and works in Berlin, Germany. He holds a BA from the Chelsea College of Art and Design, London, UK, and studied at Konstfack University of Arts, Crafts and Design, Stockholm, Sweden. Anholt’s work was the subject of the solo presentation "Time Machine" at Kunstverein Ulm, Germany (2018) and featured in group presentations at the Marciano Art Foundation, Los Angeles, CA (2023); Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Germany (2020); and KH7 Artspace, Arhaus, Denmark (2018). His work is held in numerous public collections, including the Collection Majudia, Montreal, Canada; Marciano Art Foundation, Los Angeles, CA; and M Woods, Beijing, China.

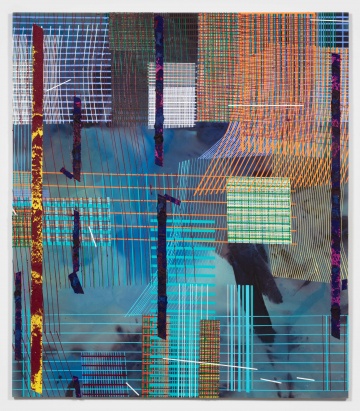

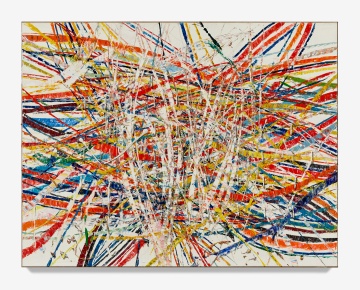

Sam Moyer

Circles of Confusion

November 4, 2023 - December 16, 2023

BLUM is pleased to present "Circle of Confusion," Brooklyn-based artist Sam Moyer’s first solo exhibition with the gallery.

“The circle of confusion” is a term used in photography and film to define and measure what is in or out of focus in a picture. It is an area where a point of light grows to a circle that you can visibly see in the final image, in which the size of the circle determines the sharpness of the image.

In the circle of confusion, ideas come in and out of focus. The closer and smaller the idea, the more acute and sharp the opinion, the action; the broader and wider the scope is, the blurrier the feelings, the greater the overwhelm and failure to process, but still an understandable image—all within the circle of confusion.

I started making these paintings in 2020 as a solution to a problem. It was a moment when the broader scope was too hard to hold. The narrowing of focus to the work of brush strokes and intuitive response tightened the circle of confusion for me. Since 2020, the circle has expanded and contracted. As I write this, I am feeling overwhelmed again, grateful for this task to sharpen focus.

These paintings have a limited palette centered around Payne’s Gray, a color that represents the cold reflective light of “magic hour,” the moment after the sun has set, before it’s dark—when the light is a soft blue. This in-between light emphasizes contrast while simultaneously flattening the world.

I never studied painting. I have sort of forged my way through this new relationship with oil paint via advice and guessing, but the material has revealed a direct tactile play with light that I have always sought from the existing surfaces of materials. In photography and stone, a relationship to light is inherent to the process, or comes directly from the source, but with painting, I have the control. Utilizing different techniques of application, I can get the surface of the paintings to reflect or absorb light in configurations that are only revealed as the viewer walks around the work, engaging the body, returning the painting to its objecthood and its relationship to the three-dimensional world, and sculpture.

The images and patterns of the paintings exist in my mind in a form of haunting. Another circle of confusion, they hold a soft edge while in the realm of imagination and tighten as I start the actual work of laying down paint. I pull focus through process, allowing the material to aid in the work’s direction.

Upstairs, seven new photographic works are on view. The images in this series are of eroded sea walls that were built on the beaches of Gardiners Bay on Long Island, using the stones of the beach as the aggregate in the concrete mixture. As time and water have moved over them, the structure of the walls has degraded into free-formed shapes. They have lost their protective function but, in so, have been transformed into site-specific sculptures— a collaboration between the human hands that made the walls and the forces of nature that have been breaking them down.

I have framed the photographs in concrete using the same beach stones as aggregate. The frames take on the role of representing what these forms once were, holding the image of their trajectory.

—Sam Moyer

Sam Moyer (b. 1983, Chicago, IL) lives and works in Brooklyn, NY. She earned her BFA from the Corcoran College of Art and Design, Washington, DC, and her MFA from Yale University, New Haven, CT. Her work has been featured in national and international exhibitions such as at the Drawing Center, New York, NY; the Bass Museum, Miami, FL; University Art Museum, University at Albany, NY; Public Art Fund, New York, NY; White Flag Projects, St. Louis, MO; Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, MO; LAND, Los Angeles, CA; and Tensta Konsthall, Stockholm, Sweden. Moyer’s work is held in numerous prominent collections, including the Aïshti Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon; Davis Museum, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA; Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris, France; Morgan Library & Museum, New York, NY; Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY; and the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT.

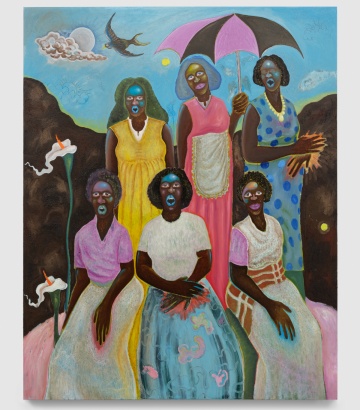

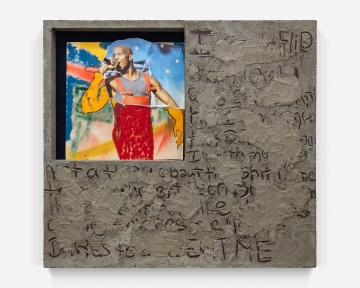

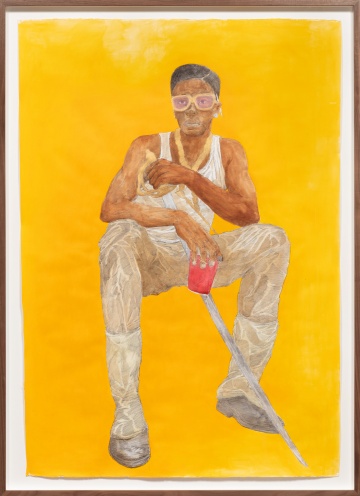

Simphiwe Ndzube

Chorus

November 4, 2023 - December 16, 2023

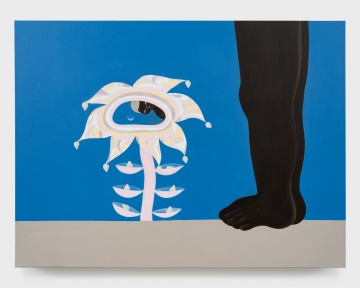

BLUM is pleased to present "Chorus," Los Angeles-based artist Simphiwe Ndzube’s first solo exhibition with the gallery.

Expanding the reaches of his surrealist Mine Moon universe—the fictional location that has long functioned as the setting for the artist’s otherworldly vignettes—"Chorus" sees Ndzube adding new tropes and mark-making techniques to his visual lexicon. Where Ndzube would previously adhere multimedia objects to acrylic on canvas, in this exhibition, he perfects his use of oil paint through carving, manipulating finishes to convey a pointillist effect, or adding sand to build out from the canvas. The artist’s subject—Black choral music traditions in South Africa—serves as a vehicle, advancing Ndzube’s storyline and making space for new painterly techniques.

Growing up in post-apartheid Cape Town, the artist has long been inspired to represent the underrepresented individuals who exist within systems of oppression—those who go unheard. Chorus marks the debut of a new series in which Ndzube explores the notion of the voice, both literal and figurative. Black choral music traditions in South Africa are deep-seated and proved to be a pivotal tool for expressing resistance during apartheid. "Amakwaya," a type of South African choral music, refers to a traditional Zulu choir that promotes Zulu culture, incorporating indigenous percussion instruments and styles. Chorus is the first installment in a new series that Ndzube has titled "Amakwaya," as it takes the culture and imagery associated with musical stylings of the same name as its subject matter.

"Chorus’s" use of oil paint is relatively new within the artist’s established oeuvre. Ndzube had previously favored acrylic for its quick drying precision and vibrance. For the artist, oil paint aligns with the fantastical qualities inherent in music in that it is more mercurial, malleable in its finish, and able to be manipulated for longer periods of time. These properties are on full display in Ndzube’s smaller-scale canvases "Chorus #1," "Chorus #2," and "Chorus #3" (all 2023)—the vibrantly colored robes of the chorus members ripple and pop where the artist has intervened to create a dimple-like effect in his paints. The theme of gestalt echoes through these three works, as well as the whole show, in that each figure is at once immediately recognizable as well as visually divisible into a multitude of innovative and intricate marks on canvas.

While Ndzube introduces many new techniques and ideas in "Chorus," he also returns to some of his powerful recurring imagery such as a flower that is both lotus and calla lily, the corpse flower, and boats at sea—all of which played major roles in his most recent solo institutional exhibition at the Denver Art Museum. These forms act as anchors for the Mine Moon—establishing the viewer in Ndzube’s surrealist universe and its critique of apartheid and the residuals of colonialism. In "Dead Father, A Cry Song for the Nation." (2023), Ndzube depicts a chorus of mourners in the Mine Moon, where the lotus and calla lily hybrid flower is native fauna, as they grieve the death of anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko.

"Chorus" indicates a major turning point for Ndzube. It is his first solo exhibition with BLUM, debut of the "Amakwaya" series, and the premier of these new techniques and personal symbols. The combination of these elements conveys visually the audible experience of music—its associated customs and inherent whimsical qualities—as well as continues to build the artist’s distinct perspective within the magical realist discourse as a new source of recourse against structures of injustice.

Simphiwe Ndzube (b.1990, Eastern Cape, South Africa) lives and works in Los Angeles, CA and Cape Town, South Africa. He received his BFA from the Michaelis School of Fine Arts in 2015. Recent solo exhibitions include "Oracles of the Pink Universe," Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO (2021); "The Rain Prayers," Museo Kaluz, Mexico City, Mexico (2019); "Bhabharosi," The Rubell Family Collection, Miami, FL (2018); and "Waiting for Mulungu," CC Foundation, Shanghai, China (2018). His installation "In the Land of the Blind the One Eyed Man is King?" (2019) was included in the 2019 Lyon Biennale. His work is collected by the Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO; Fondation Gandur pour l'Art, Geneva, Switzerland; HOW Art Museum, Shanghai, China; Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA; Musée d’art Contemporain de Lyon, France; Rubell Museum, Miami, FL; Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, Cape Town, South Africa; among many others.

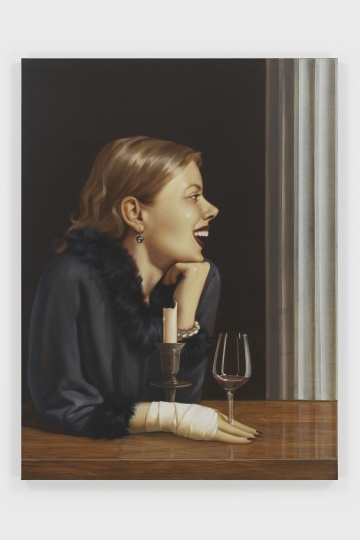

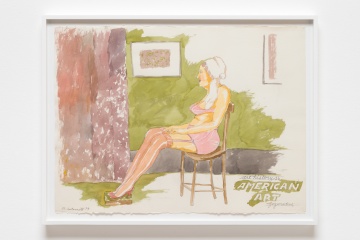

Curated by Alison M. Gingeras

"Pictures Girls Make": Portraitures

September 9, 2023 - October 21, 2023

Blum & Poe is pleased to present “‘Pictures Girls Make’: Portraitures,” an exhibition bringing together over fifty artists from around the world, spanning the early nineteenth century until today. Curated by Alison M. Gingeras, this prodigious survey argues that this age-old mode of representation is an enduringly democratic, humanistic genre.

“Pictures girls make” is a quip attributed to Willem de Kooning who purportedly dismissed the inferior status of his wife Elaine’s portrait practice. [1] Inverting the original dismissal into an affirmation, “Pictures Girls Make” is a rallying cry for this exhibition which examines how different forms of portraitures defy old aesthetic, social, and ideological norms.

Both historically and contemporarily speaking, the portrait has always been far more than a rendering of a specific person’s likeness. Portraiture engages with ideas of identity, subjectivity, and agency. Moving beyond binary thinking, the exhibition strives to emphasize the diversity of subjects, complexities of biography, and array of individual characters that artists have been able to capture through various modes of portrait making.

Gatekeeping through Genre

Gatekeeping is as old as art itself. For centuries, the policing of pictorial genres has been an effective means of wielding power and enforcing artistic hierarchies along gender, race, and class lines. In the Western European tradition, portraiture was the reserve of the elite: executed by a specialized cadre of male artists and supported through commissions by the aristocracy, the clergy, and merchant classes. Despite the hegemony of the genre’s origins, a close re-reading of the history of portraiture and its continued vitality has overturned its privileged, homogenous foundations.

“It is very wonderful that a woman’s picture should be so good,” proclaimed Albrecht Dürer in 1521 after first learning about the existence of painter Susanna Horenbout. Those rare women artists who gained professional stature in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were often disparaged as “copying” their male peers, revealing “the weakness of the feminine hand” as critics remarked of Dutch Golden Age artist Judith Leyster when she was compared to her male counterparts. Impressionist artist Marie Bracquemond, who was trained by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, wrote in her diary, “The severity of Monsieur Ingres frightened me… because he doubted the courage and perseverance of a woman in the field of painting… He would assign to them only the painting of flowers, of fruits, of still lifes, portraits and genre scenes.” Relegating women artists to “minor” art forms as well as essentializing claims about ALL women painters’ inferior skills have shaped the art historical canon for generations. Fifty years of feminist art historical scholarship has only recently begun to successfully push back against the gatekeeping that has kept women—and non-white European—artists in the shadows.

Elaine de Kooning was no stranger to this type of gender/genre policing. Her distinctive portraiture practice was a direct response to the gatekeeping at work in her own artistic partnership. While she was a rare postwar artist that would confidently oscillate between figuration and abstraction, Elaine de Kooning embraced portraiture—“pictures that girls made”—as her chosen genre. Against the backdrop of Abstract Expressionism’s macho bravura, Elaine de Kooning was compelled to stake out autonomous ground. Her distinctively brushy, expressive portraits were a powerful riposte to her husband’s gendered gatekeeping.

Drawing upon revisionist histories that have uncovered forgotten or repressed artists, as well as through the range and diversity of artists working today, it can be argued that portraiture has always been an enduringly democratic, deeply humanistic genre. Both historically and contemporarily, portraiture has the capacity to capture a multitude of subjectivities, identities, and agencies. What was once considered a lesser form of painting, portraiture must be understood as a powerful vehicle for exploring human complexities. Portraiture was and is made by painters of every possible race, ethnicity, caste, and sexuality. They are also made by gender-fluid, non-binary artists. Straight white men still make them. Portraits are pictures people make.

Old Portraits, New Canons

At least historically speaking, the de Koonings were righter than they realized. Portraits are pictures girls make—going all the way back to the sixteenth century. The Flemish painter Caterina van Hemessen made the first-ever self-portrait as an artist at her easel in 1548—giving birth to a crucial genre of the palette self-portrait, the ultimate means of asserting artistic legitimacy and self-promotion. In her wake, Sofonisba Anguissola, Lavinia Fontana, Artemisia Gentileschi, and Élisabeth Louise Vigée LeBrun, among other Old Mistresses, have made emblematic contributions to this genre while asserting their authorship and professional standing.

Catalyzed by feminist scholarship, a new canon forged from old portraits has emerged: forming the conceptual core of “‘Pictures Girls Make.’” Pictures of really important girls. This exhibition is an homage to these Old Mistress foundations. Specially created for “‘Pictures Girls Make,’” Chris Oh’s painting on antique glass, entitled “Spectacle” (2023), reprises Sofonisba Anguissola’s iconic self-portrait (1556) at her easel with brush and maulstick in hand. Acknowledging this new art historical canon, Oh’s work poignantly pays homage to the pioneering role women artists have historically played in this specific and powerful form of self-representation—a trope that is extensively explored in a range of studio self-portraits. These include an important self-portrait by Mela Muter—the first professional Polish-Jewish artist—who depicted herself in her Montparnasse studio (1915); June Leaf’s studio scene “Broome Street (Sheila in the Studio)” (1969-70); and Somaya Critchlow’s fictionalized, nude self-portrait “X Studies the work of Pythagoras” (2022). Ranging in style from Surrealism and magical realism to more quirky, cartoony styles, a number of powerful artist self-portraits constitute an important trope in the exhibition with works by Gertrude Abercrombie, March Avery, Joan Brown, Robert Colescott, Juanita Guccione, Sally J. Han, Agata Słowak, and Katja Seib, among others.

Identity Politics: A Double-Edged Sword

The complex impact of identity politics on artistic discourse is at the heart of “‘Pictures Girls Make’”—particularly the many ways in which identity-based organizing has promoted diversity, demanded equality of representation and opportunity, raised awareness of specific group struggles, and have forced changes to socio-political power structures. Yet while a motor for political and representational change, identity politics presents a double-edged sword—something that is sometimes played out in the instrumentalization and oversimplification of portraiture. The sometimes-reductive nature of identarian thinking often flattens complexity—boiling down discussion of an artwork to checking a box of gender, race, or sexuality—obscuring other meanings, aesthetics, and potential universal human values contained within the work.

A critical ambivalence about the progress and limits of identity politics thus informs this exhibition. How can portraiture function both as an emblem of social change and simultaneously be considered as an autonomous, complex painting that speaks to the history of art in its own right? Or in the words of Kerry James Marshall, “How do you address history with a painting [whose subject] that doesn’t look like Giotto or Géricault or Ingres, but without abandoning the knowledge that painters had accumulated over the centuries?” Speaking about the duality of Marshall’s contribution to representations that exceed the reductionism of identity politics, Carroll Dunham writes, “[Marshall is able to] simultaneously occupy a position of beauty, difficulty, didacticism, and formalism with such power.” As these two artists’ thoughts attest, the entwinement of formal and conceptual complexity is the only way to evade the oversimplification and pigeonholing of portraiture’s importance when discussed only through an identity politics lens.

Catalyzed in large measure by the urgency of the Black Lives Matter movement, the art market, alongside museums, have rapidly embraced Black artists over the past few years—particularly emphasizing Black figurative painters. Whether spurred by political awakening or cynical opportunism, the race to foreground “new” artists of color has been driven mostly by a narrow focus on Black subject matter, while egregiously ignoring the complex histories of artists of color. This amnesic approach to contemporary Black artists has mostly overlooked the crucial handful of artists of African ancestry working in Africa, Europe, and America who were known before the twentieth century—the seventeenth-century painter Juan de Pareja, the Neoclassicist Guillaume Guillon-Lethière, Henry Ossawa Tanner, and sculptor Edmonia Lewis are notable exceptions.

“‘Pictures Girls Make’” pays homage to this history by featuring an important early portrait by Joshua Johnson (1763-1824), the earliest known African American professional artist. A formerly enslaved, freeman of color, Joshua Johnson eventually made a career as a portraitist in Baltimore where his clients were among the city’s vibrant merchant and middle classes. “Portrait of a Woman” (date unknown) portrays a now-unknown white lady who is dressed in her finery. The portrait features all the hallmarks of Johnson’s signature style—finely rendered details like her lace collar, her facial features and jewelry as well as a distinctive palette. Including Johnson’s work along with “Portrait of a Creole Gentleman” (circa nineteenth century) by an unknown artist of the Louisiana School [possibly a follower of Julien Hudson (1811-1844)] is intended to be a genealogical gesture that gives some context to a range of twentieth and twenty-first-century artists of color who have taken up the portraitist mantle—from twentieth-century trailblazers like Benny Andrews, Ernie Barnes, and Winfred Rembert, to twenty-first-century artists like Patrick Eugène, Andrew LaMar Hopkins, Danielle Mckinney, Umar Rashid, and many others who draw upon their predecessors. “‘Pictures Girls Make’” will also include a selection of portraits by contemporary African artists such as Nigerian artist Chidinma Nnoli, South African artist Simphiwe Ndzube, and Ugandan artist Collin Sekajugo.

Who Gets Portraitized?

“People’s images reflect the era in a way that nothing else could,” proffered Alice Neel when speaking about her devotion to the genre. “When portraits are good art they reflect the culture, the time, and many other things…art is a form of history.” Neel was among a generation of artists who radically changed who got portraitized, and by extension, which histories were enshrined for posterity on canvas. Neel immortalized her Leftist comrades, working-class families, her neighbors in Spanish Harlem, heavily pregnant women, and queer artist friends. In the same spirit, many twentieth-century artists such as Benny Andrews, Maria Anto, Jerome Caja, Leonor Fini, Yannis Tsarouchis, and Léonard Tsuguharu Foujita painted individual subjects, groups or communities, allegorical or archetypal figures, or even themselves. Most of their sitters were not traditionally represented in mainstream art history.

Looking backwards and forwards, “‘Pictures Girls Make’” will recontextualize a number of pioneering portraitists who escaped the narrow first draft of the past century as well as also surveying a wide range of contemporary painters. Far from “just girls,” an unprecedented diversity of contemporary artists who engage with portraiture have pushed the genre to capture the actual conditions, social structures, and day-to-day experiences that make up contemporary life while innovating a range of formal painterly languages.

[1] This quote was first cited in Lee Hall, “Jaunty” in: Maria Catalano Rand, “Elaine de Kooning Portraits” (Brooklyn: The Art Gallery, Brooklyn College, 1991): p. 21.

“‘Oh, yes,’ she said, speaking of Bill de Kooning, ‘Now, he wouldn’t consider painting portraits. I mean,’ she said, ‘Bill just always thought that portraits were pictures that girls made. So,’ she said, ‘I made portraits. I had that area free; I had it to myself; I didn’t have to make decisions. I knew I was going to make a portrait and It[sic] didn’t much matter of whom: once you are set to make a portrait, you’re free to make a painting.’”

There is some question about the context and tone in which Willem de Kooning purportedly made this comment—it is possible that it was made in jest or with an ironic tone—though the sexism of that era has been well-documented and has been the subject of much scholarship.

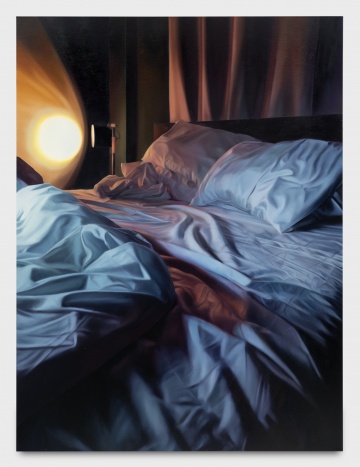

Christopher Hartmann

Nightswimming

July 1, 2023 - August 12, 2023

“The sun had not yet risen. The sea was indistinguishable from the sky, except that the sea was slightly creased as if a cloth had wrinkles in it. Gradually, as the sky whitened a dark line lay on the horizon dividing the sea from the sky and the grey cloth became barred with thick strokes moving, one after another, beneath the surface, following each other, pursuing each other, perpetually.”

—Virginia Woolf, “The Waves”

Blum & Poe is pleased to present “Nightswimming,” London-based artist Christopher Hartmann’s first solo exhibition with the gallery.

Hartmann’s paintings portray situations that are seemingly detached from specific time and space. These settings often imply physical interaction or dialogue but are imbued with conflicting moods of intimacy and alienation, the indistinct yet persistent feelings of unease latent to our oversaturated media landscape, and technology-mediated social connections. The construction of the painting itself mimics the layering processes of photo-editing software, with the built-up application of artificial color tones recalling the alienating luminosity of digital screens.

This exhibition focuses on Hartmann’s interest in abstraction, beginning with a series of beds that appear to have just been left. These works evoke the vulnerability of sleep, the ambiguities of dream states, and the intimacy of physical relationships. Loaded with a heightened sense of emotion and reality, they inhabit a liminal space between fact and fiction, the reality of the present and memory of the past. The bed paintings are presented in dialogue with two seascapes. The myriad folds in the bedsheets mirror in the infinite ripples on the water’s surface, intimating different states of immersion—the consciousness suspended during sleep and the body suspended in water.

The sense of absence conjured by the works in the first gallery gives way to the gradual introduction of a bodily presence in further paintings that alternately explore intimacy and isolation. One depicts two pairs of legs aligned within the rippling folds of white sheets. Another two show figures lying alone, their body language alternately inviting and more guarded. Subtly larger than life yet intimate and relatable, the looming perspectives of these compositions implicate the viewer as more than a merely detached observer. The final body of work on view presents close-ups of entwined hands, concluding the exhibition with gentle moments of touch bathed in natural light.

Christopher Hartmann (b. 1993, Germany) is a German-Costa Rican artist living and working in London. He holds an MA in Communication Design from Central Saint Martins, London, UK and completed his MFA in Fine Art at Goldsmiths, University of London, UK in 2021. He is a recent grantee from the Elizabeth Greenshields Foundation (2020) and resident of The Fores Project, London, UK (2020) and Nassima Landau Foundation, Tel Aviv, Israel (2022). Solo exhibitions of Hartmann’s work include “State of Life, May I Live, May I Love,” T&Y Projects, Tokyo, Japan (2022) and “What I Want to Say Is This,” Nassima Landau Foundation, Tel Aviv, Israel (2021). Selected group exhibitions include “Queering the Narrative,” Neuer Aachener Kunstverein, Aachen, Germany (2022); MFA Fine Art Degree Show, Goldsmiths, University of London, UK (2021); High Voltage, Nassima Landau, Tel Aviv, Israel (2020); and London Grads Now, Saatchi Gallery, London, UK (2020).

Acaye Kerunen

A NI EE (I AM HERE)

July 1, 2023 - August 12, 2023

Blum & Poe is pleased to present the gallery’s first solo exhibition with Ugandan artist Acaye Kerunen, her first solo presentation in the United States. This American debut follows Kerunen’s acclaimed showcase in Uganda’s inaugural national pavilion at the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy in 2022, which received the biennale jury Special Mention award for best national participation.

Drawing the viewer into Kerunen’s immersive, cross-disciplinary practice—one which includes visual art, curation, activism, acting, poetry, writing, and performance—this exhibition emphasizes a multifaceted approach to triumphant noncompliance in a postcolonial world. Stitching, appending, twining, and knotting several commissioned works into inclusive wholes, Kerunen drives her platform home via her means of production, imagery, and materiality.

Aligning the process of its own production with activism in the service of environmentalism, resistance to colonial and patriarchal tendencies, and the dismantling of hierarchies that devalue women’s labor—Kerunen’s work addresses the greater good from the moment it is conceptualized, before it is even presented in the exhibition space. Taking a stand against climate change, the artist’s process includes communal living and materials sourced in the wetlands of her motherland, Uganda. Employing techniques Kerunen learned from her mother and the matriarchs before her, the artist constructs her work from coils of woven natural fiber that are articulated by women in her community. The individuals and philosophies called upon to make the work are living extensions of the art objects they produce, as the systems and utopias they create serve as Kerunen’s ever-evolving counterpoints against problematic structures of power.

Kerunen’s physical objects ground the artist’s oeuvre, serving as touchstones and points of entry for the viewer to investigate the other, more transitory portions of the artist’s work such as her activism, production as a form of social practice, and performance. In this exhibition, the artist uses recurrent imagery to drive home the messages of resistance that she has emphasized throughout her practice. The form of the butterfly is alluded to in “Nyakotha - The one who flys off” (2023). The butterfly’s process, beginning as a caterpillar, is one that Kerunen uses to convey sentiments of transformation and growth. In other sections of the exhibition, Kerunen similarly uses repeating tropes such as the colors black and white to indicate unified division and mappings of her own body to explore the emotions ingrained in her various stances.

Beyond the physical object and its means of production, Kerunen also engages in time-based and intangible mediums to achieve her end. As part of this exhibition, the artist deploys the moving image. This video work, an intangible media that is a relatively new form within the plastic arts, illustrates the way Kerunen has prioritized elevating types of art making that challenge the traditional canon. Whether using techniques that had been pigeonholed as craft or creating work that is partially evanescent, Kerunen’s force for change rings true in her wide-ranging choice of media.

Layer upon layer of consideration and meaning is embedded in every inch of this exhibition. Each object, activation, or communication has been imbued with heritage, sentiment, and hope for a better future—from sustainable materials to partial articulation by underserved communities, impactful compositions to intangible practices. All these messages commingle—unifying in a resounding chorus—to chip away at and call attention to social orders that perpetuate inequity.

Acaye Kerunen’s (b. Kampala, Uganda) work was showcased in the two-person exhibition “Radiance: They Dream in Time” in Uganda’s inaugural national pavilion at the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy (2022) which received the biennale jury Special Mention award for best national participation together with France. She presented her first solo exhibition, titled “Iwang Sawa,” at the Afriart Gallery, Kampala, Uganda (2021). That same year, the artist participated in a curatorial fellowship supported by Newcastle University; Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda; 32° East, Kampala, Uganda; and Afriart Gallery, Kampala, Uganda. In 2018, she showed her interactive, collaborative installation “Kendu” (2018-present) at the Nyege Nyege Ugandan Culture and Music Festival. The artist holds a BS in mass communication from the Islamic University in Uganda, Mbale, Uganda. Kerunen lives and works in Kampala, Uganda.

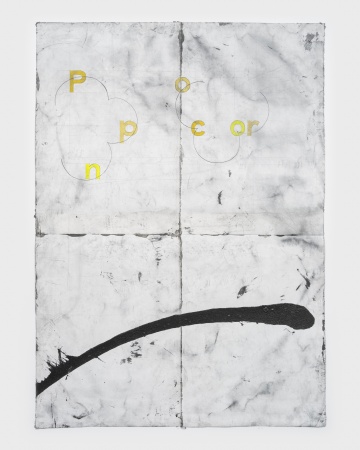

Matt Saunders

The Distances

July 1, 2023 - August 12, 2023

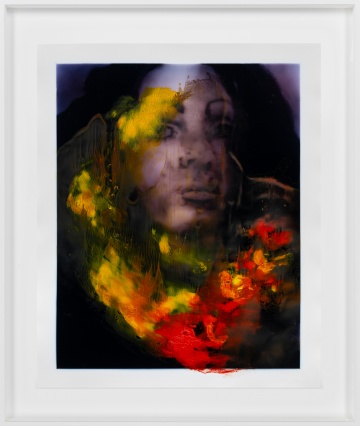

Blum & Poe is pleased to present “The Distances,” American artist Matt Saunders’s fourth solo exhibition with the gallery and his first in Los Angeles since 2014.

Exploring the open border between painting and photography, “The Distances” sees Saunders delving further into his ongoing study of liminal spaces in the dividing lines that dictate visual art’s medium specificities. In pointing to the limitations of these categorical barriers, the artist engages with other observed dichotomies—proximity versus distance, immediacy versus mediation, or gaze versus counter gaze. Painterly gestures atop the photographic surface evoke touch and contact while vacillating between convergence and divergence with the image below.

Oil paint has long been behind Saunders’s photographic process. It now takes the forefront. Each of Saunders’s works for “The Distances” begins with an oil painting on thin chiffon. Configured as a negative, wherein white is black and colors are inverted, these stretched paintings are taken into a darkroom and used to strain light onto photosensitive paper to make each photographic image. The resulting prints are brought back into the studio where paint is thoughtfully applied to their surface, thus the image comes together from both sides of the photo’s process. “The Distances (Joe)” (2022) shows well the steps behind its making. Vibrant aqua interventions press forward on the picture plane, partially obscuring an expressive, almost photo-realistic face.

At each stage of his practice, Saunders activates an encounter between the image and the material that captures it. This chain of transference is not separate from the meaning of the work, which calls up themes of overlap, transformation, and the fluidity of constructed social categories such as gender. Humanizing these exchanges, the eyes of Saunders’s emotive subjects gaze upon the viewer as they are also gazed upon, almost daring equal and opposite perception. The artist created the bulk of these works in the solitude of the pandemic when the interpersonal seemingly became a lost art. In dialogue with his teaching, Saunders reflected on the performative and fluid versions of gender experienced by each generation; thus, the subjects in “The Distances” return to many of the foundational muses who he painted early on in his career. With this revisitation, he creates a channel through to his early work—marking his own stylistic transitions from early to midcareer.

Matt Saunders (b. 1975, Tacoma, WA) is based between New York, Boston, and Berlin. He currently serves as a full Professor of Art, Film and Visual Studies at Harvard University. Recent solo exhibitions include “Currents 114: Matt Saunders,” Saint Louis Art Museum, St. Louis, MO (2017); Tank Space, Shanghai, China (2017); “Century Rolls,” Tate Liverpool, UK (2012); and “Parallel Plot,” Renaissance Society, Chicago, IL (2010). Saunders was the 2022 recipient of the American Academy of Arts and Letters Arts Purchase Prize, 2015 Rappaport Prize from the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, 2013 Prix Jean-François Prat and 2009 Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation award. His work is represented in numerous public collections, including the Deutsche Bank Collection; Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, MA; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.; Istanbul Museum of Modern Art, Istanbul, Turkey; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; MUDAM, Luxembourg; Museum Brandhorst, Munich, Germany; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA; Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY; Saint Louis Art Museum, St. Louis, MO; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY; Tate Modern, London, UK; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY; and the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT.

Thornton Dial

Handwriting on the Wall

April 29, 2023 - June 10, 2023

Blum & Poe, in partnership with the Estate of Thornton Dial, is pleased to present the gallery’s first solo exhibition showcasing the work of late artist Thornton Dial—his first major presentation in Los Angeles.

Renowned for his innovations, Dial developed an unprecedented style by fusing gestural virtuosity with a spiritual commitment to found materials—a panoply of cast-off goods and items considered valueless or broken. Drawing on traditions not taught in formal institutions—the yard shows of the American South, patchwork quilting, and the gospel church—he created a visual and narrative language that reframes important moments in world history and encapsulates the Black experience in the American South during the artist’s lifetime. The resulting works balance personal, cultural, and universal meanings to give voice and imagery to systemic inequities both past and present. This retrospective exhibition takes viewers on a journey backwards in time through twenty-eight years of Dial’s career painting venerated retellings of Black American history—from slavery to Jim Crow and through the election of the first Black president.

Like many of the works presented in the initial gallery, “Garden of Eden” (2015) is making its first ever public appearance. Painted in the artist’s last year of life, this work provides valuable insight into Dial’s reflections on his own mortality. As indicated in its title, “Garden of Eden” is a rumination on death—the Judeo-Christian Bible tells the story of Adam and Eve, the first humans, becoming mortal only when expelled from the garden. Painted in a contrasting palette of lilac, yellow, and grey, life’s impermanence is depicted here as neither good nor bad, but a swirl of both. Layering a single piece of fabric atop the spraypainted enamel on canvas over wood—an exercise in succinctness compared to the found-object assemblages from Dial’s earlier career—“Garden of Eden”’s construction also indicates the artist’s perception of his body’s mobility. Key symbols in the biblical tale include the tree of life, which allowed Adam and Eve eternal life, and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, which produced fruit whose consumption resulted in Adam and Eve’s expulsion from divine paradise. “Garden of Eden”’s composition is primarily abstract, except for a single, nearly indiscernible houseplant. In the artist’s oeuvre, it is common to see seemingly mundane objects imbued with great meaning—as with this plant of humble origins that, here, represents both eternal life and the pathway to death. Ever an optimist, even while considering his own imminent passing, Dial creates a new allegory with this painting. He alludes to his own origins—born in a cornfield to an unwed teenage mother and working a half-century building highways, houses, and boxcars—to convey the great contributions that he and other Black voices have made in the realms of racial advocacy and culture despite having faced innumerable challenges along the way.

In an adjacent room, a midcareer work titled “Hot and Cold (Life in the Rolling Mill)” (1995–96), exemplifies a through line from Garden of Eden to the artist’s earlier interest in the tenderness and humanity found in unlikely places. Representational of the artist’s signature assemblages, “Hot and Cold (Life in the Rolling Mill)” is an impressive symphony of scrap metal, wire mesh, fabric, clothing, carpet, a fly swatter, a toy tractor, twine, artificial hair, Splash Zone compound, spray paint, and enamel on canvas over wood. In this case, a steel mill acts as a lens through which to examine romantic relationships. Before becoming a full-time artist, Dial held a series of industry jobs, most notably working at the Pullman-Standard plant in Bessemer, Alabama for thirty years making boxcars. “Hot and Cold (Life in the Rolling Mill)” uses the steel forging process, in which the metal is heated to a very high temperature to make it malleable before being dropped into water to quickly cool and retain its shape, as a metaphor for the unpredictable nature of love. A man, constructed from scrap metal and bearing a mustache that resembles the facial hair Dial wore for much of his life, reaches toward a woman of the same material constitution wearing lipstick and a dress. Frozen in their move toward one another, the two never fully touch—a stance that recalls Michelangelo’s “Creation of Adam” and prompts a reconsideration of the nature of partnership.

Relationships—between individuals, economic classes, genders, and races—have always been a key theme in Dial’s oeuvre. In an oil on canvas painting titled “Running with the Mule, Running for Freedom” (1990), presented here alongside his earliest works, the artist paints a Black man riding a mule and flanked by onlookers. In his early work, Dial often used animals to embody the othering, everyday ordeals of Black Americans. For a Black factory employee working in Bessemer around the time of the second Selma march, expressing opinions on racial inequity could have resulted in a loss of livelihood—or life. In “Running with the Mule, Running for Freedom” the mule is a symbol of the historic associations of Black Americans with work animals, commodities, and disposable labor. The mule is also a reference to Dial’s ancestors who, for generations, were sharecroppers on the plantation where Dial was born. The white figures in this work, not subject to the mule’s associations, look on with expressions of shock and sadness, indicating that Dial held out hope for interracial collaboration to overcome Black oppression.

Dial was a documentarian and orator of his own lived experience at a time of great tumult and change in his community. Beyond his important insights into twentieth-century Black life and culture, Dial’s work—from the beginning of his career as an artist to the end of his life—provides an astute and moving meditation on love, death, and the desire for more than one’s allotment. Reflecting on his contributions to art and culture, Dial said, “Since I been making art, my mind got more things coming to it. The more you do, the more you see to do... I believe I have proved that my art is about ideas, and about life, and the experience of the world.”

Thornton Dial’s (b. 1928, Emelle, AL; d. 2016, McCalla, AL) work has been the subject of numerous solo exhibitions at institutions across the nation, including the Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts, University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL; traveling to Samford University Art Gallery, Birmingham, AL and Wiregrass Museum of Art, Dothan, AL (2022–23); Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, OH (2020); High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA (2016); Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN (2011); New Orleans Museum of Art, New Orleans, LA (2011); Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX (2005); New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, NY (1993); American Folk Art Museum, New York, NY (1993); and was included in the Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum, New York, NY (2000). Dial’s work is represented in the permanent collections of the American Folk Art Museum, New York, NY; Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY; Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, TX; de Young Museum, San Francisco, CA; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA; Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Pérez Art Museum, Miami, FL; Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture, Washington D.C.; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY, among many more.

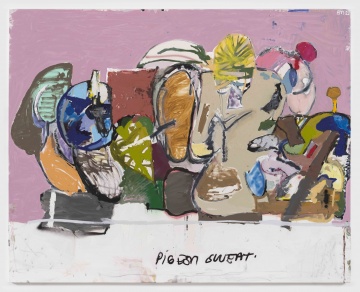

Lonnie Holley, Louisiana Bendolph, Hawkins Bolden, Joe Light, Ronald Lockett, Joe Minter, Rita Mae Pettway, and Mary T. Smith

By Any Means Necessary

April 29, 2023 - June 10, 2023

Blum & Poe is pleased to announce “By Any Means Necessary,” an exhibition curated by Atlanta-based artist Lonnie Holley and featuring work by Holley, Louisiana Bendolph, Hawkins Bolden, Joe Light, Ronald Lockett, Joe Minter, Rita Mae Pettway, and Mary T. Smith. This presentation accompanies “Handwriting on the Wall,” the first major exhibition in Los Angeles focusing on the work of Holley’s close friend and colleague, Thornton Dial, and honors their shared histories and passions. This show is presented in conjunction with “Lonnie Holley: If You Really Knew” at MOCA North Miami, Holley’s first major exhibition in the South and featuring work from this same cohort of artists he champions including Thornton Dial, Mary T. Smith, and Hawkins Bolden.

“As an artist, it’s an honor to curate my first serious show on the occasion of my dear friend Thornton Dial’s first exhibition in Los Angeles.

This show, which also includes my own work, is a tribute to some of the many voices that cried out in the wilderness for so long. All the artists in the show—Louisiana Bendolph, Hawkins Bolden, Joe Light, Ronald Lockett, Joe Minter, Rita Mae Pettway, and Mary T. Smith—were or are dear friends of mine and Mr. Dial and created works of art for the same reasons that we have: as a testimony about our lives and experiences growing up in the harsh reality of the South.

We all used different materials or means, based on what was available to us—the fabric scraps turned into patchwork quilts by Louisiana Bendolph and her mother, and many others in Gee’s Bend, Alabama; the found objects that Joe Minter transformed; or the tin from old barns that were recycled by Ronald Lockett and turned into something beautiful—all were used by us in our daily lives. We took something that had been discarded or cast aside and tried to give it new meaning and purpose, much the same as we tried to do with our own lives. I dedicate this show to William Arnett, who had the vision not only to support so many African American artists, but also to help us learn that we were part of something larger and that what we were doing really mattered.”

— Lonnie Holley, 2023

Louisiana Bendolph (b. 1960, Gee's Bend, AL) is an American quilt artist known for intricate compositions of an almost architectural or conceptual character and striking formal inventiveness. Bendolph’s instantly recognizable style exemplifies her lifelong immersion in the deep structures of design and pattern. Born and raised in Gee's Bend, Alabama, she learned her art at the feet of many women ancestors, including her mother (Rita Mae Pettway) and grandmother, who passed down to her their community’s generations-old, and now world-famous, quilting traditions. Bendolph works in other media, as well, including a 9’ x 16’ ceramic mural commissioned in 2015 by the San Francisco International Airport. Her quilts have been exhibited throughout the world and are in the permanent collections of numerous museums. She lives and works in Mobile, AL.

Hawkins Bolden (b. 1914, Memphis, TN; d. 2005, Memphis, TN) was a found-object sculptor from Memphis, TN. A childhood accident left him blind, able to sense only the presence of light, and ended his boyhood dreams of professional baseball. As an adult, Bolden created anthropomorphic “scarecrows” for his home garden in inner-city Memphis. These objects (he did not use the term “art”) range from minimal, mask-like forms to large, totemic constructions. They incorporate discarded metal cookware, garden tools, furniture, construction materials, appliances, machine components, and other scrapyard finds. These works are further elaborated with garden hoses, clothing, limbs of artificial Christmas trees, carpet scraps, shoe leather, toys, and other odds and ends, and are strategically patterned with punched holes that suggest human facial features such as eyes and mouths.

Lonnie Holley (b. 1950, Birmingham, AL) is based in Atlanta, GA. Holley's artworks encompass an expanse of mediums, including sculpture, drawing, painting, collage, and digital, as well as musical performance. His musical style is likewise diverse, blending blues, jazz, spoken word, funk, and folk idioms. His work has been celebrated for its complex storytelling and insights into issues of race, class, social justice, environmental disaster, and the transformative potential of art itself. Holley’s work has been the subject of numerous solo exhibitions including at Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami, FL (2023); Dallas Contemporary, Dallas, TX (2022); Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, NY (2021); Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, Atlanta, GA (2017); Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art; Charleston, SC (2015); Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, AL (2004), and many more. His work is represented in major public collections worldwide including Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY; among many others.

Ronald Lockett (b. 1965, Bessemer, AL; d. 1998, Bessemer, AL) was an American visual artist. Born and raised in Bessemer, AL, he came of age after the civil rights movement had radically remade the political and economic landscape for Black Americans and for Lockett’s home region, the American South. Lockett’s artistic practice often explored the experience of “belatedness”—that is, of arriving too late to participate in the epic deeds and historic accomplishments of earlier generations. His “Traps” series, for example, uses whitetail deer, a species that has managed to survive amid human development and encroachment, as a proxy for himself and his Black peers whose lives felt immobilized by larger social forces. Lockett eventually gave up representational painting almost entirely to focus on compositions of cut tin, a unique process he developed by scavenging from the postindustrial environment of his Bessemer neighborhood. Lockett died in 1988 of complications from AIDS.

Joe Light (b. 1934, Dyersburg, TN; d. 2005, Memphis, TN) was an American painter and assemblage artist who worked in Memphis, TN. Light’s art combines elements from throughout pop culture, especially comics and cartoons, along with a debt to the genres of still life and landscape painting, with a strong affinity for the desert vistas of the American Southwest. Light encountered many of his influences during years of dealing bric-a-brac in flea markets, where he bought and sold everything from mass-produced kitsch to reproductions of well-known paintings from throughout the Western tradition. He ultimately invented a full-blown visual language to express his religious and moral convictions, using a personal iconography that includes flowers, mountains, rivers, birds, abstract glyphs, various alter egos, and signage. Light’s philosophical beliefs took shape in the 1960s, during a period of incarceration, when he converted to Judaism—more specifically, the texts and principles of the Old Testament, independent of formalized religion—through which he discovered guidance for navigating the challenges of life as a Black man in the modern American world. Light’s paintings are held in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., among others.

Joe Minter (b. 1943, Birmingham, AL) is an American sculptor and painter, based in Birmingham, AL, who is best known for a sprawling, outdoor art environment that he calls “African Village in America.” In 1989, Minter began building a sculpture garden (next to a Black cemetery where his family members are interred) as a memorial to what he terms the “foot soldiers” of the civil-rights movement—its unheralded change-agents. In the decades since, his vision has expanded to address issues of human rights and environmental justice on an international scale. Minter’s signature style mixes found-object assemblage and welded scrap metal, frequently accompanied by hand-lettered texts and bold, vivid paintings. With wit and optimism, his works juggle trenchant political commentary and a deep love of the natural world, all inspired by his Afrocentric worldview. Minter’s art is in the permanent collections of museums throughout the United States.

Rita Mae Pettway (b. 1941, Gee's Bend, AL) is a quilt artist from Gee’s Bend, AL. From age four, after her mother’s death, Pettway was raised by her grandparents and aunts, who taught her to quilt. Her grandmother Annie E. Pettway produced some of the most important surviving Gee’s Bend quilts of the Depression era and served as a crucial artistic mentor to Rita Mae. Annie was reportedly fastidious about technique and craftsmanship but possessed an open-ended, freeform attitude toward pattern and composition. Rita Mae created her first full quilt at age fourteen and has carried forward the aesthetic principles imparted by her accomplished ancestors. Her daughter, Louisiana (Pettway) Bendolph, has in turn taken these approaches into new frontiers of design. Pettway’s quilts have been widely exhibited and are represented in museums including the Virginia Museum of Art.

Mary T. Smith (b. 1904, Copiah County, MS; d. 1995, Hazlehurst, MS) was an American painter whose powerfully expressionist images of herself, her family and friends, plants and trees, and her pets and animals were created to adorn her home and roadside property in Hazlehurst, MS. Born in Copiah County, MS, she was the daughter of sharecroppers and grew up under segregation in the Jim Crow South. Essentially deaf since childhood, she was briefly married, had one child, and worked as a domestic servant. Smith lived alone and turned to painting later in life as a way to both identify and express herself to the world. She created nearly all of her surviving paintings in her seventies and eighties. While her themes are often local in their evocation of day-to-day existence, and at times devoutly religious in their proclamation of divine love and care, her paintings’ mix of personal humility and stylistic boldness possesses a tacitly political resonance. Smith’s paintings are in the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and other institutions.

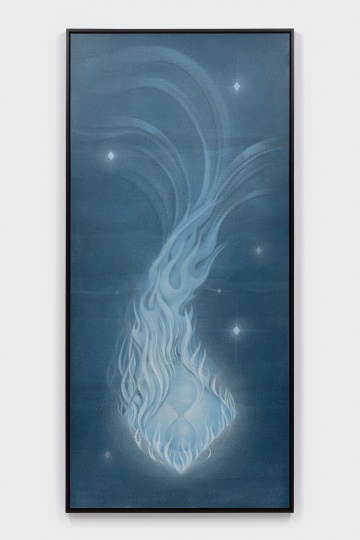

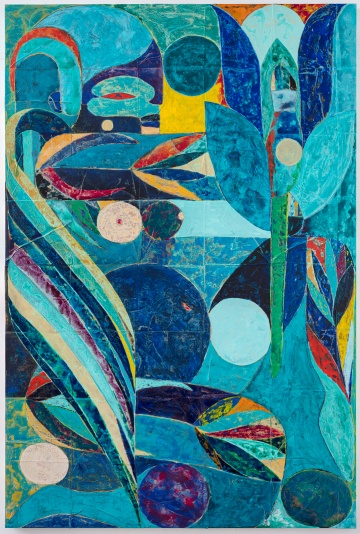

Asuka Anastacia Ogawa

pedra

March 11, 2023 - April 15, 2023

Blum & Poe is pleased to present “pedra,” Los Angeles and New York-based artist Asuka Anastacia Ogawa’s fourth solo presentation with the gallery.

This exhibition finds Ogawa diving further into her ongoing investigations of the spirituality that pulses though the natural world, the artist’s studies in ikebana, and the foremost religions in Japan. In the works presented here, Ogawa deploys her signature, childlike figures, depicting them in scenes of quiet meditation or rituals centered around natural talismans. Drawing on her knowledge of polytheist and animist practices in Japan and Brazil—where Ogawa spent her formative years—the artist paints a hyperbolized magical world filled with spiritual guides and plants with supernatural powers. This altered reality heightens and underscores the cultural overlaps in the artist’s experience, calling attention to the hyper-globalized state of the world and Ogawa’s encounters with reconciling multiple sociological influences.

Ogawa’s smaller paintings set the tone for this exhibition, emphasizing the significant attention paid to earthly forms: a red flower cranes in front of an olive-toned background. In her larger compositions, the artist’s characters have made potions or incenses that they apply to themselves and others as part of traditional Brazilian or Japanese customs. By ingesting botanicals or using them on their bodies, the players in Ogawa’s narrative oeuvre begin to merge with the natural world.

The artist’s depiction of practices involving organic totems foregrounds communion between humans and the earth—a central theme of this exhibition. For Ogawa, some of these rituals are personally witnessed accounts and some are imagined extensions of the cultural phenomena that she encountered living in Japan and Brazil. As the child of a Brazilian mother growing up in Japan, Ogawa recalls that her mother would often pray to angels. While only two percent of the Japanese populous identifies as Christian, the artist notes taking comfort in seeing her mother keep this practice. In “mochi” (2023) a figure shrouded in pink raises an offering of the Japanese rice cake mochi to the heavens.

Further threading the needle between religious practices in Brazil and traditions in Japan, “open” (2023) depicts a shaman and another figure flanked by flowers as they pray against a deep amethyst backdrop. In Japanese worship, it is commonplace to make offerings of flowers or food to the local shrine or the place of prayer in the home. Ogawa paints these floral offerings to nature, known as “kuge,” throughout the exhibition as her own form of reflective meditation and as a means of archiving this devotional practice.

Hinted at through backdrops derived from a dark and shadowy color palette, this new series offers weighty reflections on a personal period of change and growth for the artist. This transition, Ogawa notes, was catalyzed by her own encounters with these depicted rituals and traditions, which offered a deeper understanding of human nature and her own spatial roots.

Asuka Anastacia Ogawa (b. 1988, Tokyo, Japan) spent much of her childhood in Tokyo, Japan. When she was three years old, Ogawa moved from this vertical urban backdrop to rural Brazil, where she passed a handful of formative early years amongst wandering farm animals and rushing waterfalls. The artist later relocated to Sweden when she was a teen, where she attended high school, and soon thereafter she moved to London to pursue her BFA from Central Saint Martins. After having her first solo show at Henry Taylor’s studio in Los Angeles, CA in 2017, she had a solo show at Blum & Poe, Tokyo in 2020, Blum & Poe, Los Angeles in 2021, and Blum & Poe, New York in 2022. Her work is in the collection of the Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, TX, the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham NC, and X Museum, Beijing, China. She is currently based in Los Angeles, CA and New York, NY.

Julian Hoeber

I Went to See Myself but I Saw You

March 11, 2023 - April 15, 2023

Blum & Poe is pleased to present "I Went to See Myself but I Saw You," Los Angeles-based artist Julian Hoeber’s eighth solo exhibition with the gallery.

Many of the works presented in "I Went to See Myself but I Saw You" deploy geometric motifs, a device that Hoeber has used throughout his career, as part of a new series structured around the concept of stereoscopic vision—the process of seeing three-dimensionality derived from two eyes operating independently of one another. The paintings and sculptures presented here emulate this phenomenon, creating image pairs that are both unexpected and nuanced. These image pairs, placed side-by-side on a single panel or sculpture, expose the visual gymnastics required to see with two inputs: an experience that is both functional and imperfect. By hyper-focusing on and reframing the act of seeing, one begins to understand their perception of the world as fallible and constructed.

Hoeber has a long-demonstrated interest in giving physical form to cerebral or internal experiences. Since the artist’s first exhibition with Blum & Poe in 2002, "Killing Friends," he has investigated the breakdown of inner versus outer and persistently exposed the faulty nature of popular cultural dichotomies. Beginning in 2020, Hoeber began researching and making paintings inspired by the work of Sir Charles Wheatstone. In 1838, Wheatstone invented the Wheatstone stereoscope, a device allowing independent right-eye and left-eye views at the same time. With this viewer, one could create the conditions for binocular rivalry: wherein the mind will try, often with great difficulty, to reconcile the two different images that it is seeing. Under these circumstances, human cognition triggers a contingent and shifting pattern of overlay between the two vignettes. Hoeber recreates this experience in the wall-mounted sculptures presented here, such as in "What Two Animals Are Most Alike?" (2023), which depicts both a rabbit and a duck. Depending on the viewer’s position, "What Two Animals Are Most Alike?" transforms—becoming part-rabbit and part-duck as the mind struggles to meld the input that it is receiving from each eye.

Both the Wheatstone stereoscope and Hoeber’s investigations manipulate the act of looking to bring the viewer closer to understanding how the outside world is internally processed. Robert Smithson also cited Wheatstone’s stereoscope as a major influence on his two-part sculptural work "Enantiomorphic Chambers" (1965)—the studies for which are in the collection at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Of this sculpture, Smithson said, “To see one’s own sight means visible blindness.” In response to this statement, and to the work presented in "I Went to See Myself but I Saw You," Hoeber states, “I’d say that seeing one’s sight (something I agree is at the center of experiencing the Wheatstone viewer) is not so much visible blindness as necessitating a revision of regular sight as less trustworthy. I’m trying to get people right up to the surface of the contingency of their own vision.”

In these works, Hoeber looks back at the history of painting, realizing that the single-point perspective used in the Renaissance period was meant to create a seamless and cohesive space by leaving out the complexities of what it is to truly see through two eyes. Binocular vision has two vanishing points that are made obvious when bifurcated by a device such as the Wheatstone viewer. The paintings that Hoeber presents in this exhibition each have two vanishing points, forcing onlookers to encounter them in steps—first one side, then the other. When interfacing with the geometric forms and small orbiting moon of "28 Days or 17 Miles" (2022), the eye is drawn to each side of the composition. This is the case with all of the paintings presented here, due to the artist’s recurrent use of multiple vanishing points. When confronting these paintings up close, the spectator naturally gets pushed to either side of the work, depending on which portion they are looking at. Hoeber offers this experience to the viewer—intending each panel as a device to produce this kind of two-part looking.

"I Went to See Myself but I Saw You" resists Western picture making’s propensity for depicting a cohesive vision of the world. Hoeber acknowledges that these more traditional works leave out a great deal of complex information—for example, how the simple act of human sight actually goes through many steps in its journey from exterior to interior perception. In bifurcating the single vanishing point in his works through the logic of Wheatstone, stereoscopic vision, and binocular rivalry, Hoeber evokes an element of the sublime—an existential jolt that causes one to reconsider their own way of perceiving the world. As the artist puts it, “I’m interested in the idea that viewers and viewing are always slippery and a bit fractured.”

Julian Hoeber (b. 1974, Philadelphia, PA) holds a BA in Art History from Tufts University, Medford, MA, a BFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, and an MFA from the ArtCenter College of Design, Pasadena, CA. Hoeber’s work is featured in public and private collections internationally including Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, TX; DESTE Foundation for Contemporary Art, Athens, Greece; de Young Museum, San Francisco, CA; Francis Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery, Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, NY; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA; Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY; Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas, TX; Palm Springs Art Museum, Palm Springs, CA; Rosenblum Collection, Paris, France; Rubell Family Collection, Miami, FL; and the Western Bridge Museum, Seattle, WA. Julian Hoeber lives and works in Los Angeles, CA.

Magdalena Skupinska

Fertile Plate

March 11, 2023 - April 15, 2023

Blum & Poe is pleased to present "Fertile Plate," London-based artist Magdalena Skupinska’s first solo exhibition with the gallery.

Skupinska’s work draws from modernist traditions of biomorphic abstraction, arte povera, and minimalism to facilitate a reconnection with the essential multi-sensory experiences that stimulate the basis of our being. Deeply rooted in her surroundings, Skupinska’s work draws from a process of research and experimentation into the flawed, but present, symbiotic relationship between human and non-human forces in our shared world.

The artist created this body of work as a collage of feelings, ideas, places, and sensations that manifested through intuition and stream of consciousness. Skupinska cites literature discussing flora, botanical medicine, and her own day-to-day relationship to plants as a major inspiration for her work. The resulting paintings are viewed by the artist as a collaboration between herself and the natural world.

Skupinska’s abstract compositions emerge from the coming together of dynamic hues of paint formulated by the artist with purely organic materials, free of artificial substances. When concocting her paints, Skupinska’s ingredients range from ginkgo biloba, blue spirulina, to activated charcoal, and her selection is guided by varying intentions. A decision could be provoked by a color, a healing or nourishing property of a plant, the artist’s personal relationship with a plant, a texture, a scent, or simply intuition. Often, the different qualities—hue, meaning for the artist, or consistency—of disparate plants come together to create a single image.

Time plays an important role in the creation of these works. Only when her paint dries does Skupinska know the true color of her paints due to her natural paint-making process. Even still, some paint mixes undergo a maturation process long after their application. Tests and experimentations are necessary to find the right botanical blend. Color is also of paramount importance to Skupinska in that it reflects the essence of the plants and their respective multi-sensory elements. In emphasis of the role that color plays in her work and its inherent relationship to the natural materials within her paints, Skupinska also stains the wood of her frames with corresponding plant mixes. This exhibition unites the artist’s encounters with the natural world—cataloging her endeavors as a botanist and relaying her musings on the symbiosis between humans and plants.

Magdalena Skupinska (b. 1991, Warsaw, Poland) completed her BA in Fine Art at Central Saint Martins, London, UK and her MA in Painting at Royal College of Art, London, UK. She has participated in residencies at Selebe Yoon, Dakar, Senegal; Fundación Casa Wabi, Oaxaca, Mexico; La Ira de Dios, Buenos Aires, Argentina; and the Atlantic Center for the Arts, New Smyrna Beach, FL. Her work has been the subject of international solo exhibitions and a monograph released in 2022.

Friedrich Kunath

I Don't Know The Place, But I Know How To Get There

January 14, 2023 - February 25, 2023

“Abendlied” by Hanns Dieter Hüsch

Butterfly is coming home

Little bear is coming home

Kangaroo is coming home

The lights aglow, the day is done.

Codfish is swimming home

Elephant is walking home

Ant is racing home

The lights aglow, the day is done.

Fox and goose are coming home

Cat and mouse are coming home

Man and woman are coming home

The lights aglow, the day is done.

All is asleep and all is awake,

All is in tears and all is laughter,

All is silence and all is chatter,

And sadly, we’ll never know it all.

All is screaming and all is listening,

All is dreaming and then in life,

All will be replaced again one day.

Already the evening sits atop our home,

Butterfly is flying home

Wild horse is bolting home

Older child is coming home

The lights aglow, the day is done.

Friedrich Kunath (b. 1974, Chemnitz, Germany) studied at the Braunschweig University of Arts, Braunschweig, Germany and now lives and works in Los Angeles, CA. Kunath utilizes a personal style of romantic conceptualism, layering poetic phrases with poignant, often melancholy imagery. The work embraces comedy and pathos, evoking universal feelings of love, hope, longing, and despair. The artist’s personal journey from Germany to Los Angeles plays a key role in his work, incorporating German Romanticism and western popular culture, with still life, cartoon imagery, commercial illustration, nature photography, and lyrical references.

The first major monograph devoted to Kunath’s life and work was published in 2018 by Rizzoli Electa, featuring contributions by James Elkins, James Frey, Ariana Reines, and John McEnroe.

Kunath has been the subject of numerous solo exhibitions including "I’ll Try to Be More Romantic," Kunstsammlung Jena, Germany (2021); "Juckreiz," Sammlung Philara, Düsseldorf, Germany (2016); "A Plan to Follow Summer Around the World," Centre d'art Contemporain d'Ivry - le Crédac, Ivry-sur-Seine, France (2014); "Raymond Moody's Blues," Modern Art Oxford, UK (2013); "Your Life is Not for You," Sprengel Museum, Hannover, Germany (2012); "Lonely Are the Free," Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin, Germany (2011); Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA (2010); Kunstsaele, Berlin, Germany (2010); "7 x 14," Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden, Germany (2009); and "Home Wasn't Built in a Day," Kunstverein Hannover, Germany (2009). His work is also featured in prominent public and private collections such as the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, PA; Centre Pompidou, Paris, France; DESTE Foundation for Contemporary Art, Athens, Greece; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA; Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA; Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, CA; Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY; Pinault Collection, Paris, France; and the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN, among many more.

Alma Allen

January 14, 2023 - February 25, 2023

Blum & Poe is pleased to present Mexico-based artist Alma Allen’s fourth solo exhibition with the gallery. This show coincides with Allen’s solo museum presentation at Anahuacalli Museum in Mexico City.

Alma Allen is an American-born sculptor known for his orchestration of arresting gestural immediacy and distinctive material engagement, meticulously carved and cast to draw attention back to the work itself. This presentation marks the debut of Allen’s wall-hanging bronze reliefs. Works ebb and flow in both their shape and color, with reflective surfaces in a high-polish shine or patinas of a painterly soft black. Like rushing water, these sculptures spill out from their station on the wall, reaching toward the viewer, then recoiling back. Calling to mind the peaks and valleys of landscape and body, they offer both a muscular materiality and fluid sense of the expanded experiential plane. Centered amongst the bronzes is a single stone sculpture carved into shiny pleats from a local marble, revealing hues of rose, milk, and umber. Whimsical in form, oblong like a pickle or an eggplant, the soft shape of the work belies its notable weight, a suggestive joke within an abstract charge.

In the adjacent garden stands a tall bronze among greenery—a visceral courtship of chaos, it twists in upon itself, both gleaming outwardly and withholding its innermost contents. Like a banyan tree, a bundle of twine, or the fibrous tissue that unites muscle with bone, the strands of this work seem to reflect objects from the natural world in a manner both familiar and infused with intimate notation. Its banded construction may very well reference the flowing lava produced by the eruption of Xitle, a volcano that destroyed Cuicuilco, one of the many pre-Hispanic cities that preceded Mexico City.

In preparation for both this and his upcoming museum presentation, Allen explored parallels in his work and in Diego Rivera’s approach to designing the Anahuacalli Museum, his final work. On Rivera’s vision for the pyramid-like building built over lava flow, the museum states that his “genius lay in his ability to recognize... a unique combination of environmental features that constitute an identity that is inseparable from location: rock, earth, breath, blood, the quality of light.” Throughout Allen’s multi-leveled practice, these same qualities are flooded with a psychological valence. Within the collision of elements in Allen’s work is rooted a distinct series of repeated, recognizable gestures that allow poetics, mythologies, and narratives to emerge within the timeless qualities of sculpture and material.

Relocating from Joshua Tree to Tepoztlán in 2017, Allen’s work has expanded into and absorbed his new environs, responding to the energetic forces near his studio. His proximity to Mexican stone quarries permits Allen to work directly not only in the carving but the selection of material. Along with his bronze foundry, Allen’s long dedication to making his work within his own studio has expanded craft notions of the handmade and cemented his reputation as a modern steward of classical sculptural techniques. This exhibition captures a recent chapter and takes it to its natural pinnacle—as Allen continues his exploration of symbolism and existential volatility in intricate forms whose weight, balance, and presence reconcile transient physicalities and inner visions against the eonic span.